Where the Money Lives: Mapping Viable Markets for Interior Designers in the U.K.

Feb 13, 2026This post is about money, geography, and a question that most interior designers think about but rarely see addressed directly:

Where in the UK are there enough affluent households, concentrated closely enough together, to make running a residential interior design practice a genuinely viable commercial proposition?

By the end of it, I'll share a ranked leaderboard of 27 areas across the country - from the obvious (Central London) to the less obvious (Burnham Market, Aldeburgh, Prestbury) - showing where these golden zones sit.

But to get there, we need to talk first about what I call the affluence threshold: the household income level below which interior design simply does not feature in people's spending, no matter how much they might want it to. That means a short detour through some economic data.

Stay with me...it matters, and the payoff is worth it!

The demand side - what does interior design cost?

UK interior design fees range from £50 per hour for consultancy-only services up to £50,000+ for large-scale luxury renovations. A realistic mid-market residential project - say one or two rooms with a design-only package - sits at roughly £500 to £5,000+ per room. A full-service project typically charges 10-20% of the project budget, or £5,000 to £50,000+.

So a modest but meaningful interior design engagement - the kind that keeps a sole practitioner busy and fairly paid - probably starts at around £3,000-5,000 in fees for a single-room project, and more realistically £8,000-15,000 for a multi-room scheme. Add the client's own spend on furniture, finishes and labour, including the designer’s procurement costs and charges, and the total project cost (not including construction) is likely £30,000-100,000+.

The Big Question: The income side - so, who can afford that?

We're going to talk about median incomes, the middle value when you line up all the data points in order. If you have 100 households ranked by income from lowest to highest, the median is the income of household number 50. Half earn more, half earn less.

It's used instead of the mean (the average) because very high earners skew the average upwards and make it misleading. If nine people earn £30,000 and one earns £500,000, the mean is £77,000 - which describes nobody in the group. The median is £30,000, which is far more representative of the typical experience.

Median household disposable income after housing costs in 2023/24 was £2,780 per month in the South East (the highest), £2,670 in London, and as low as £2,265 in the West Midlands. That's roughly £27,000-33,000 per year after housing costs.

Median annual full-time earnings range from £47,455 in London to £32,960 in the North East.

A household spending £10,000 on interior design fees (plus, say, £30,000-50,000 on the project itself) is making a commitment that represents a very significant percentage of disposable income for the median household. It's really only realistic for households with incomes substantially above the median.

A Rough Guestimate:

The threshold at which residential interior design becomes commercially viable in a local market - meaning there is a sufficient concentration of households willing and able to commission design services regularly enough to sustain a sole practitioner - is probably a median household income of around £50,000-60,000 per year (gross, before tax). So we're talking about areas where half the local households earn more than £50-60K p.a That puts entry-level prospective clients roughly in the top 20-25% of UK households nationally.

In practice, that maps to London, the South East, parts of the South West (Bath, the Cotswolds corridor), pockets of the East of England (Cambridge, parts of Hertfordshire and Essex), Edinburgh, and affluent commuter towns around major cities. It also maps to specific postcodes rather than whole regions - there are pockets of affluence in otherwise lower-income areas, and plenty of lower-income neighbourhoods within London.

Below that threshold, a designer can certainly find individual clients, but the density of potential clients becomes too thin to sustain a business on local one-to-one work alone. You might earn £5,000 or £10,000 from a client one month, but then nothing more for a fair while. That's precisely the point at which decoupled income becomes not just attractive but structurally necessary. I have another post about decoupled - aka passive - income in the pipeline.

Spoiler - passive income isn't passive, and it isn't an easy answer. To be continued next week.

This is all back of an envelope stuff. The real insight is that this is a question of density, not just individual wealth. A designer in a market where, say, 5% of local households can afford their services needs a much larger geographic catchment (or a different model entirely) compared to one where 20% can. That density question is what makes location so decisive in interior design - and what makes the case for decoupling (passive) income so compelling for designers outside the affluent centres.

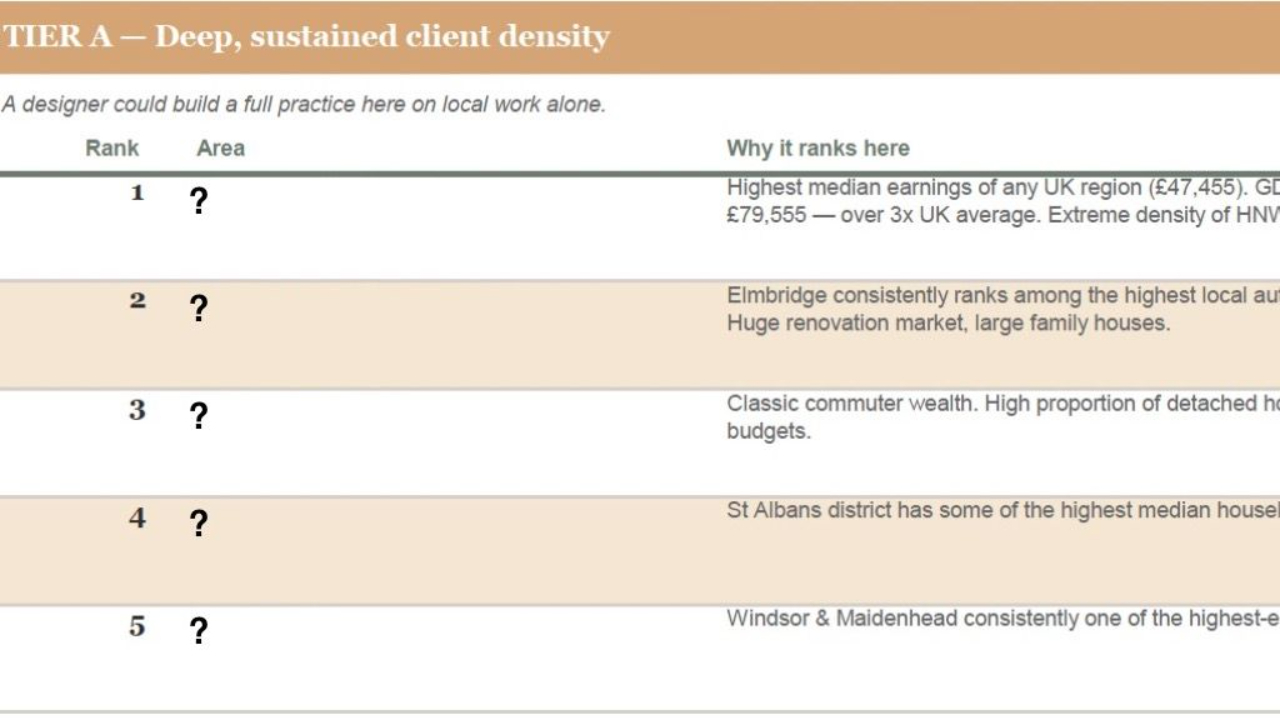

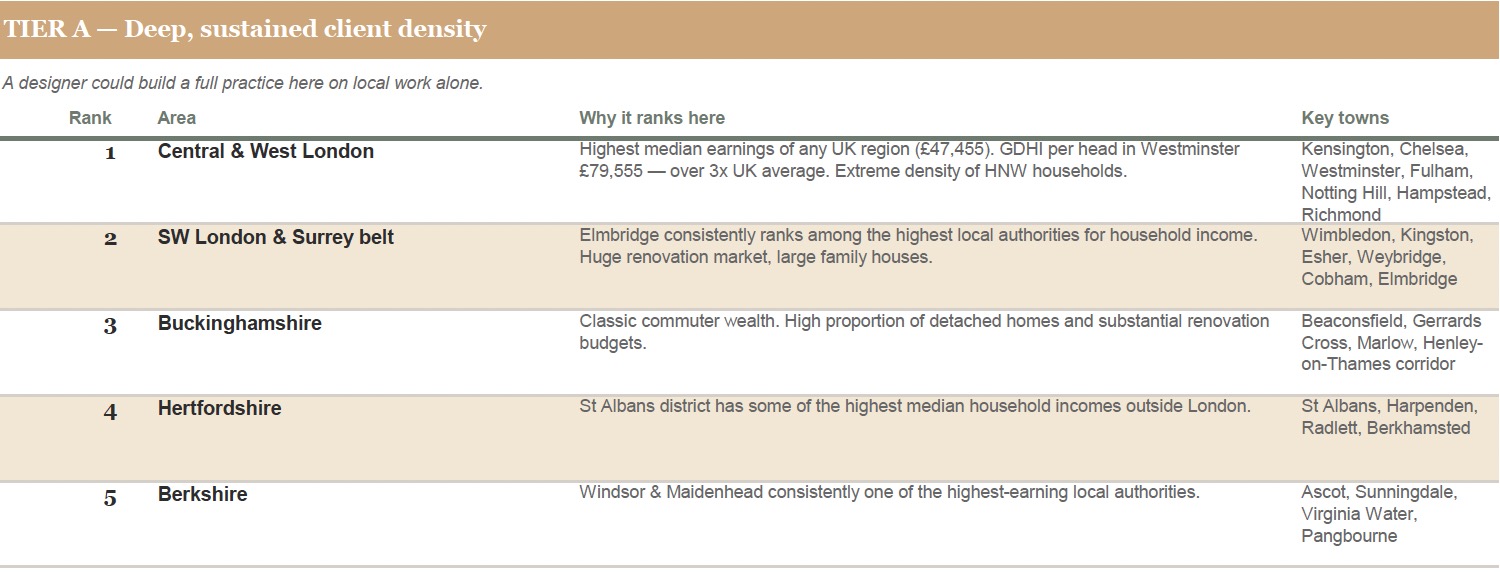

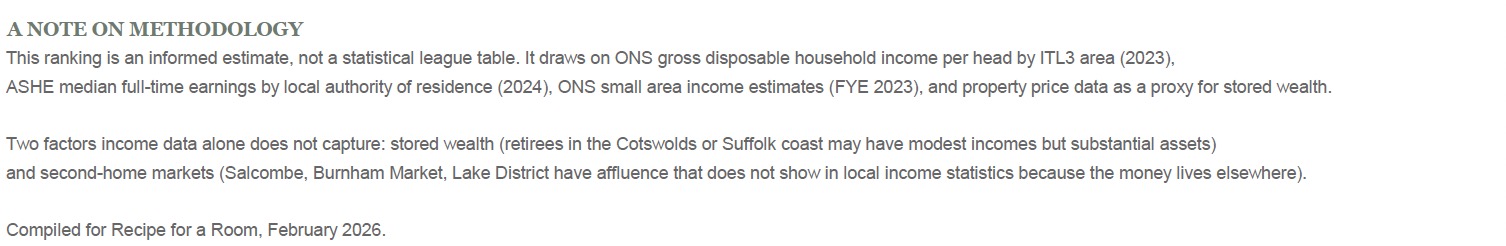

So, now to the leaderboard of affluent Britain. This spreadsheet is divided into three zones.

Tier A (ranks 1-5) are places where a designer could fill their diary from local referrals alone. The density of £50k+ households is high enough that the market sustains multiple practices in competition.

Tier B (ranks 6-14) have strong affluence but slightly less density or geographic concentration. A designer can build a good practice but may need to draw from a wider radius or neighbouring towns.

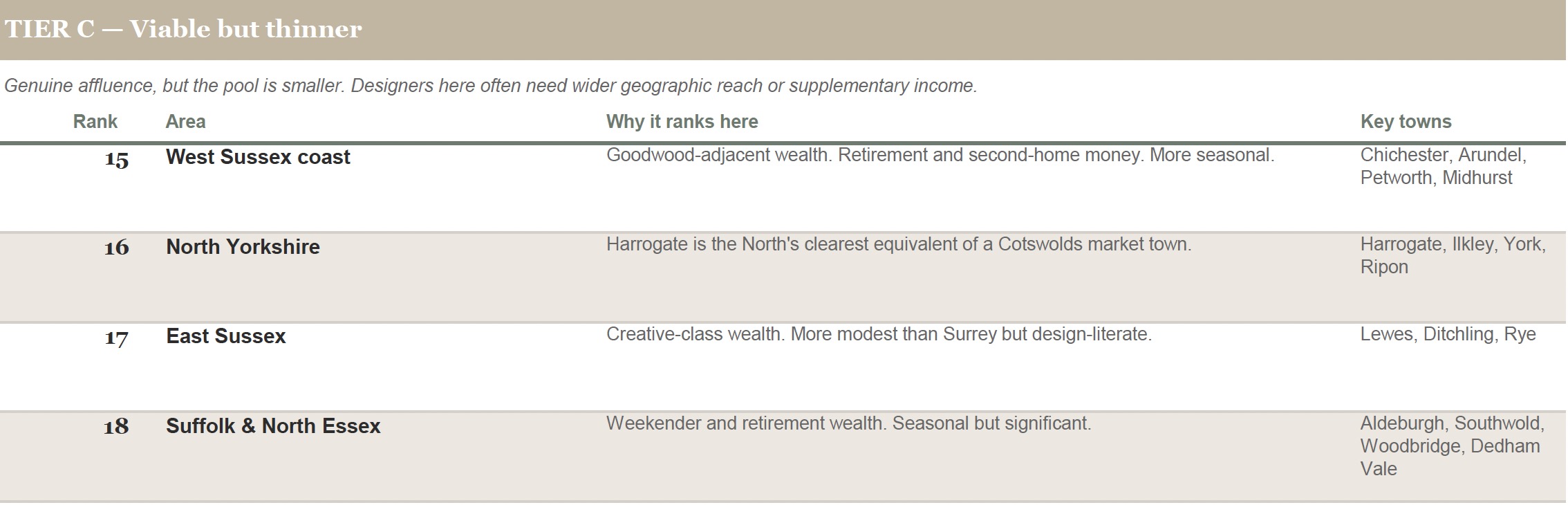

Tier C (ranks 15-27) in these locations designers may need to become creative in terms of the services and products they offer, and the argument for decoupled income becomes most pointed. These are places with real wealth - sometimes extraordinary property values - but the client pool is thin, seasonal, or dependent on a single industry. A designer based in Salcombe or Windermere faces a fundamental problem: brilliant work is possible, but the maths of one-to-one practice is precarious.

PS The AI assistant that helped to compile this report also considered but excluded places like Leeds (affluent suburbs like Roundhay exist but the density is diluted across a large city), Manchester (similar story - Hale and Didsbury are wealthy but the city-wide picture is mixed), and Cornwall (Rock and Padstow have money but it's extremely seasonal and thin).

That said, you'll notice two caveats about stored wealth and second-home markets. These are important - they explain why places like Burnham Market or the Cotswolds punch above their income statistics.

A Saturated Market?

Of course, density of affluent households is only half the equation. In the areas at the top of this leaderboard (London, Surrey, Buckinghamshire, Hertfordshire) there is no shortage of potential clients. But there is also no shortage of designers competing for them.

A strong local market attracts practices, and quickly. The question is not simply whether enough wealthy households exist, but whether yours is the practice they choose? And that is a strategic problem, not a creative one: positioning, pricing, visibility, differentiation, a clear articulation of why you and not the designer down the road.

It is exactly what my Recipe For Success Bootcamp programme is designed to address: doing everything possible, and everything ethical, to ensure that, in a competitive market, it is your business that prevails. That is the business of Bootcamp!

Next week we'll consider decoupled income - income that doesn't rely on selling professional hours to a single client - as an option for designers who don't live in or near a meaningfully affluent area.

Receive my quick-to-read weekly newsletter...

Sign up for the Hothouse Newsletter: find out what's coming up, and keep up with recent webinars, blogposts, videos, and other events - all focused on excellence in interior design practice.

We hate SPAM. We will never sell your information, for any reason.